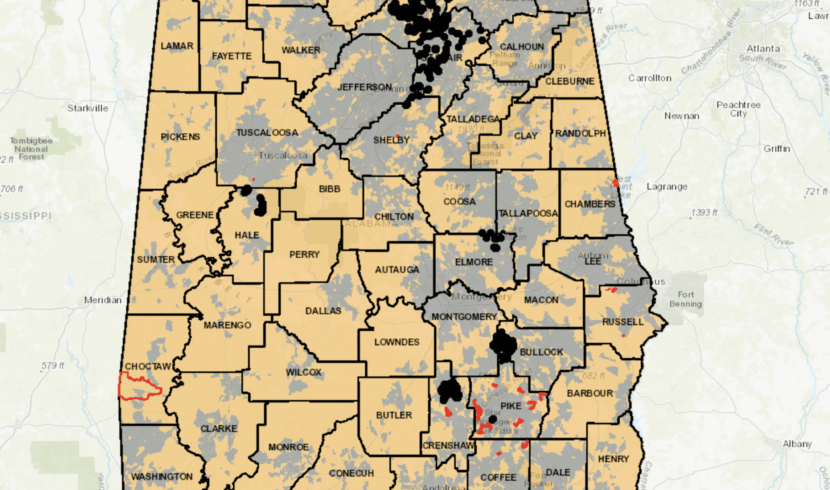

Pictured above: the latest map from ADECA showing broadband accessibility statewide. Yellow represents unserved areas, gray represents served areas, the black dots show FCC funded locations greater than 25/3 Mbps, and the red lines show projects approved in 2018. See the full interactive map via ADECA HERE.

By MARY SELL and CAROLINE BECK, Alabama Daily News

Before attempts to contain the new coronavirus sent Gulf Shores School System’s about 2,500 students home for at least two weeks, administrators asked if they have high-speed Internet there.

“With this break, we realized we have a lot of kids without access,” said Matt Akin, superintendent of the system that opened this academic year.

So, the system ordered 50 mobile hotspots to loan to students during the coronavirus-forced school shutdown. On the first day they were available, all but five were picked up. More will be ordered if needed.

“This for us is a short-term emergency response, but it’s opened our eyes,” Akin said.

“Just because you’re low income, you shouldn’t have to find a restaurant with free wifi to go do your homework,” Akin said about students’ access issues.

And now, finding free wifi in public spaces isn’t an option. As the state grapples with education, government and industry closures in response to the coronavirus, the digital divide across the state is probably the most apparent it’s ever been. Much of rural Alabama doesn’t have the infrastructure to bring broadband Internet into their homes.

“You have one-fifth of the state population that doesn’t have access,” Sen. Clay Scofield, R-Guntersville, said. “You’re essentially leaving out one-fifth of the state.”

Scofield has been an advocate in the State House for increasing broadband access through state grants.

“I’ve been saying for years (broadband access) is as important as power and water, and I wasn’t even thinking about an emergency like this.”

From the ability to work and study online to at-home medical consultations, without broadband, it’s not happening for some.

“It’s not just education. Right now, just as importantly, it is a telemedicine issue,” said Rep. Randall Shedd, R-Cullman, another advocate for increased access.

“This crisis brings it home,” he said.

On Wednesday, Senate Minority Leader Bobby Singleton, D-Greensboro, went to the Alabama Department of Public Health’s Montgomery office to get printed posters with information about the coronavirus. He planned to hang them at grocery stores and other places in his district people are visiting.

“Everything is being referenced to go to a website,” he said. “Some people don’t have access to websites.”

He said lack of broadband is a “crippling aspect” on parts of the state.

‘Significant gaps in service’

Michelle Roth, the executive director of the Alabama Cable and Broadband Association, said that populous areas like suburbs and cities have multiple broadband providers and better access because the finances are there to support it.

“The fact is that building facilities across vast rural distances, with few or sometimes no customers to help pay for that investment over time, is an extremely difficult financial and technology problem,” Roth said.

That’s why state leaders have taken action the past two legislative sessions to expand access to broadband through grants that help make it economically feasible to locate in rural areas. Still, many of those efforts are brand new and haven’t yet reached the communities in need.

In a letter to school superintendents last week, State Superintendent Eric Mackey issued guidance on what teachers could do to continue learning during the closure period. Digital or electronic learning was recommended, but the letter says that if schools are considered “open” then access to services must be equally provided to those who don’t have access to technology or students receiving special education services.

Michael Sibley, director of communications for the department of education, said any online activities offered by schools would only be considered for “enhancement” purposes and can’t be graded.

Sibley said when it comes to online education in the state, providing equity is an issue.

“There are some very significant gaps in service that trying to provide an online-only kind of education will cause,” Sibley said.

A small task force assembled by ALSDE has already met once to identify short- and long-term priorities for schoolwide operations, both functionally and instructional.

“We know there is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to schoolwide operations, so this task force will help us ensure that statewide guidance encompasses multiple facets for all of Alabama’s districts,” Mackey said.

Alabama public schools are set a re-open April 6, but school systems on the West Coast, where the virus was first detected in the U.S., have closed through most of April or indefinitely.

Mackey on Friday said he plans on giving Gov. Kay Ivey recommendations and a contingency plan by the middle of next week in case schools won’t be allowed to reopen on April 6. He said the closures will not affect students’ grades or their promotion or retention.

United States Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos announced on Friday that standardized tests and assessments can be waived due to nationwide school closures.

Mackey said during a press conference that Alabama has submitted a waiver request and that there would be no yearly report cards on schools — annual letter grades assigned each school and system — issued this fall due to the standardized tests being waived.

Increasing access

While some students likely have internet access on their phones or parents phones, that’s not ideal for homework and studying.

“It’s going to affect their education, going forward, if we have to go online,” Singleton said about the school closures and the possibility of further delayed return to schools.

Roth said the vast majority of Alabama students do have access to high-speed internet in Alabama cable providers’ service territories.

Some Alabama cable providers announced this week that they would provide no-cost and low-cost options for high-speed internet access to Alabama’s students and low-income populations.

Charter Spectrum and Comcast are providing an array of services at reduced cost, no cost for 60 days, and in some cases automatically increasing upload and download speeds for all customers going forward.

CTV Beam said for the following 30 days it will offer free 50 Mbps internet services for new customers with households including K-12 and/or college students who do not have current service.

Congressman Robert Aderholt last week sent a letter to President Donald Trump asking him to prioritize “the expeditious delivery of broadband to rural areas.”

He said in the wake of COVID-19, Americans must rely more on the Internet for telemedicine and education.

“These new realities have left millions of rural Americans who have little or no access to broadband feeling abandoned and desperately in need of help,” Aderholt said.

A map of Alabama’s broadband covered areas was released by the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs earlier this year. More than half the state’s land mass was mustard yellow, representing “unserved” areas.

In this year’s education budget, $20 million was allocated for a rural broadband access grants administered through ADECA. The same amount is proposed in Gov. Kay Ivey’s 2021 education budget. In order for an area to be counted as being “served” it has to have a minimum internet speed of 25 megabits per second for downloads and uploads of 3 Mbps. In January, ADECA had 61 applicants for state-funded grant money.

But the state’s grant program may also have a significant problem with the Federal Communications Commission. A proposed FCC rule announced earlier this year says that in order to qualify for federal Rural Digital Opportunity Fund money, entities can’t take other grants, like what Alabama is offering. Scofield is afraid providers will pick the larger federal grants, slowing the state’s local expansion efforts.

“It’s basically killing what we’re trying to do,” Scofield said.

Mike Presley, communications director for ADECA, told ADN that they were aware of the proposed FCC rule but are still trying to understand its full impact on state-funded projects.

“We are in the process of informing the entities that applied for the current round of Broadband Accessibility Fund grants that by accepting state broadband funds may make them limited in eligibility for additional FCC funds in the same project area,” Presley said.

Scofield called the proposed rule counterintuitive.

‘You’d think (the FCC would) want states to have skin in the game,” he said.

Shedd also said he’s concerned about the rule and said the state is seeking clarification on it.

Scofield said when lawmakers return to Montgomery, he’ll file a resolution opposing the rule.

Akin has been talking about students’ Internet access for about a decade. Prior to Gulf Shores, he led Piedmont City Schools and worked to get connectivity for all students there.

He said there’s no comparison to doing an algebra problem in a paper workbook on your own and doing one through an online program that can show you when you’ve made a mistake and how to correct it.

And if pencil and paper are good enough for some kids, why spend money on technology for others, Akin said.

“If you can do it on paper, why’d you buy the laptop in the first place?”

And as more coursework moves online, Akin doesn’t want some students left behind.

“To say, ‘This opportunity is not for you,’ that’s not what public education is supposed to be,” Akin said.

Roth said the COVID-19 epidemic does highlight weaknesses pertaining to the nation’s culture and economy but cable providers are still working to increase access.

“We’re continuing to monitor the situation, hear from our customers and keep finding ways to reach as many people as possible with broadband in our state during this crisis and beyond,” Roth said.

Roth also said Alabama cable providers have plans to invest more than $13 million in bringing broadband telecommunications services to rural Alabama citizens.

Eighteen grants have been submitted for funding from the Alabama Broadband Accessibility Fund that would cover nearly 8,000 Alabama homes and businesses, including 35 community anchor locations such as rural hospitals and libraries.

Other states are facing similar access issues during this coronavirus pandemic. Florida is starting to roll out “distance learning” in four counties, according to the Miami Herald. That distance learning would start on March 23 and would allow bus drivers to deliver physical tests to students who don’t have the technology to do online learning.

In California, the government has been milling around options for K-12 students who can’t complete online learning. According to EdSource, California officials are experimenting with local media outlets to deliver educational material via their programming for students who are forced to stay home. Along with the programming, the students will be delivered take-home tests that accompany the programs that will be delivered to the students via mail. For students in the area that can operate online learning, educational programming would be accompanied by online lessons and tests.

“Maybe this is an eye opener to show what the capabilities are for online learning and to ensure that every kid, whether in Gulf Shores, Greene County or Huntsville, deserves access when they go home,” Akin said.

Alabama Daily News Devin Pavlou contributed to this report.